Seosamh Mac Grianna 1900 – 1990

Tá sé gan aon amhras ar dhuine de mhórscríbhneoirí na hathbheochana; is mar seo a rinne Máirtín Ó Cadhain cur síos air um Shamhain 1949 sa léacht ‘Tuige nach bhfuil litríocht na Gaeilge ag fás?’ (Feasta, Marta 1950): ‘Níl, dar liom, gaisce mhór ar bith déanta i litríocht Ghaeilge na linne seo…. Ach bhí go dearfa triúr againn—Pádraic Ó Conaire, an Piarsach, agus Seosamh Mac Grianna— a chomhairfí ina bhfíorscríbhneoirí de réir modh measta ar bith.’ Gheofar eolas air in: A Flight from Shadow: the Life and Work of Seosamh Mac Grianna, 1999 le Pól Ó Muiri; Seosamh Mac Grianna agus cúrsaí eile, 1970 le Proinsias Mac an Bheatha ; Rí-éigeas na nGael: Léachtaí cuimhneacháin ar Sheosamh Mac Grianna, 1994 in eagar ag Nollaig Mac Congáil. Cara leis ba ea Niall Ó Dónaill agus tá a chuntas-san in Scríbhneoireacht na gConallach, 1990 in eagar ag Nollaig Mac Congáil. Ag Pádraig Ó Baoighill in Ó Ghleann go Fánaid: Gaeltacht Thír Chonaill, 2000 tá cur síos ar a shinsir agus ar an teaghlach ar dhíobh é. Tá leabharliosta ag Ó Muirí agus chuir Mac Congáil Seosamh Mac Grianna / Iolann Fionn—clár saothair, 1990 ar fáil. I gcló ag Mac Congáil in Filí agus Felons, 1987 tá cuntas Sheosaimh féin ar a shaol, anuas go dtí tuairim 1926, a chuir sé chuig Muiris Ó Droighneáin . Scríbhneoir a ndeachaigh a shaothar i gcion go mór air is ea Séamus Mac Annaidh; tá cuntas aigesean ar an gcuairt a thug sé ar Mhac Grianna in Ospidéal Naomh Conall i gcló in Rubble na Mickies, 1990. D’fhoilsigh An Clóchomhar Seosamh Mac Grianna: an Mhéin Rúin, 2002 le Fionntán de Brún a ndeir Pól Ó Muirí in ‘Tuarascáil’ (Irish Times 23 Aibreán 2003) faoi gurb é atá ann ‘an chéad mhórstaidéar acadúil atá i gcló ar a chorpus litríochta’; is é a deir an t-údar féin: ‘I dtaca leis an leabhar seo agam féin, saothar critice atá ann agus, mar sin de, tugtar eolas faoi shaol Mhic Grianna de réir mar a bhaineann sé le hábhar na tráchtaireachta.’

Deireadh sé féin gurbh i Lúnasa 1900 a rugadh é ach is é 15 Eanáir 1901 atá sa teastas beireatais a fuair Liam Ó Dochartaigh ón gcláraitheoir i Srath an Urláir (‘Mo Bhealach Féin: saothar nualitríochta’ in Scríobh 5, 1981); níor cláraíodh an bhreith go dtí 9 Feabhra 1901 agus is inspéise gur tharla mórán an rud céanna i gcás lá breithe a dhearthár Séamus Ó Grianna. I Rann na Feirste in aice le hAnagaire a rugadh Seosamh. Ba é Féilimí Dhónaill Phroinsiais a athair, a ndúirt Séamus faoi (Rann na Feirste, 1942) gurbh é an scéalaí agus an cainteoir Gaeilge ab fhearr a chuala sé riamh. Deirfiúr leis an scéalaí cáiliúil Johnny Shéamaisín Ó Domhnaill [Seán Ó Domhnaill B1] ba ea a mháthair, Máire; is é a dúirt Séamus faoin muintir a tháinig roimpisean go ndearna siad amhráin agus dánta chomh maith is rinneadh in Éirinn lena linn. Bhí deichniúr eile clainne ag an lánúin agus ina measc bhí: Domhnall Ó Grianna agus Seán Bán Mac Grianna. Col ceathracha leis Neidí Frainc Mac Grianna, scéalaí, agus Domhnall Mac Grianna, Eagarthóir an Ghúim le linn do Sheosamh a bheith ag aistriú leabhar dóibh. Is é ‘Mac Grianna’ ceartfhoirm an tsloinne. Chaith sé tamall in aontíos lena dheartháir Séamus ach ní raibh siad ag réiteach le chéile agus ba chorrach cibé caidreamh a bhí eatarthu ina dhiaidh sin.

Cuireadh bunoideachas air i Rann na Feirste agus bhí sé ina mhonatóir ann. I 1916, thug scoláireacht é go Coláiste Adhamhnáin, Leitir Ceanainn, ach níor fhan sé ann ach bliain. Chaith sé téarma de 1917 i gColáiste Cholm Cille, Doire, ach cuireadh as é; dhealródh gur mheas na húdaráis é a bheith ró-easumhal. I 1919, bhuaigh sé scoláireacht an Rí agus chaith dhá bhliain i gColáiste Phádraig, Droim Conrach, gur cháiligh mar bhunmhúinteoir. I Scoil Rann na Feirste a bhí an chéad phost aige. Tréimhse chorraithe ba ea é. Deir Pól Ó Muirí: ‘Mac Grianna’s role during the War of Independence was one of propagandist and he took no active part in the fighting.’ Scríobh sé cúpla dráma d’fhonn airgead a bhailiú d’Óglaigh an cheantair. Bhí sé in aghaidh an Chonartha Angla-Éireannaigh agus deir Pádraig Ó Baoighill go raibh sé i gcolún reatha lena dheartháir Domhnall i rith an Chogaidh Chathartha. I gcomhpháirt lena dheartháir Séamus scríobh sé dráma i 1922 mar bholscaireacht in aghaidh an Chonartha, Saoirse nó suaimhneas?? (Ó Muirí). Deirtear gurbh i ndiaidh dó An Chéad Chloch le Pádraic Ó Conaire a léamh a chuir sé roimhe scríobh i nGaeilge. Imtheorannaíodh sa Droichead Nua é i samhradh 1922 in éineacht le Séamus, Domhnall agus le deartháir eile leis, Hiúdaí, agus bhí ann go deireadh na troda. Deir Ó Baoighill go raibh sé féin agus Hiúdaí i measc na n-imtheorannaithe a bhí ar stailc ocrais i 1923. Chaith sé lár na 1920idí ag múineadh anseo is ansiúd. ‘Bhí mé tamall fada ag cuardú oibre ar fud na tíre ó 1923 go dtí 1925. . . . Bhí teastas múinteora agam i rith an ama seo agus theagasc mé coicís i dTír Eoghain go dtí go bhfuair mé mionna le tabhairt do rí na Sasana. Theagasc mé coicís eile i scoil amháin i mBaile Átha Cliath, sé nó seacht de sheachtainí i nDún Dealgan, cúpla mí arís i mBaile Átha Cliath, dhá mhí thiar i gcontae Mhaigh Eo. Anuraidh chaith mé bliain ar an Chreagán i gContae na Gaillimhe’ (as an litir chuig Ó Droighneáin); síltear gur dheacair dó post buan a fháil i ngeall ar a phoblachtachas ach síltear freisin gurbh í an mhúinteoireacht faoi deara an cliseadh néarach a bhain dó i gContae Liatroma timpeall an ama sin. Seachas cúrsaí samhraidh in Ó Méith agus i Rann na Feirste, sheachain sé an cheird as sin amach. Ó 1924 ar aghaidh, bhíodh idir aistí agus scéalta aige in: The Standard, The Irish Statesman, The United Irishman, An tUltach, Fáinne an Lae, Iris an Fháinne, Humanitas, An Camán, An Phoblacht, Irish Press. . . . Tá cuid de na haistí Gaeilge i gcló ag Mac Congáil in Ailt, 1977 agus tá a thuilleadh den ábhar, aistí, léirmheasanna, litreacha, corrdhán, idir Bhéarla agus Ghaeilge, bailithe le chéile ag an scoláire sin in Filí agus Felons, 1987, teideal a bhí ag Mac Grianna ar shraith aistí Béarla in An Phoblacht i 1926; sa chnuasach sin freisin tá aiste, ‘An Aisling’, a scríobh sé i 1953 agus a bhí i gcló in Inniu 7 Iúil 1972.

Is iad na leabhair bhunaidh a scríobh sé nuair a bhí sé i mbarr a mhaitheasa: Dochartach Dhuibhlionna agus Sgéaltaí eile, 1925 (eagrán nua ag Anraí Mac Giolla Chomhaill i 1976); Filí gan Iomrádh, 1926 (cuntas ar Dhálaigh Rann na Feirste sa tseanaimsir); An Grádh agus an Ghruaim, 1929 (gearrscéalta); Eoghan Ruadh Ó Néill, 1931 (úrscéal stairiúil); Pádraic Ó Conaire agus Aistí Eile, 1936 (eagrán nua 1986); An Bhreatain Bheag, 1937; Na Lochlannaigh, 1938; Mo Bhealach Féin agus Dá mbíodh ruball ar an Éan, 1940 (an dá leabhar faoin aon chlúdach); An Droma Mór, 1969. Thug an Gúm eagrán nua de Dá mbíodh ruball ar an Éan amach i 1993. Deir Ó Muirí gur scríobh sé úrscéal Béarla, The Miracle of Cashelmore, ach nár foilsíodh é agus nach bhfuil a fhios anois cá bhfuil an lámhscríbhinn. Deir sé freisin gurb i seilbh phríobháideach atá úrscéal eile nár foilsíodh, Réamann Ó hAnluain.

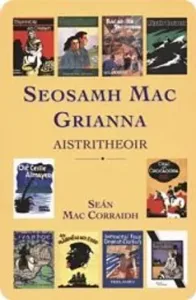

Meastar milliún go leith focal a bheith sna leabhair a d’aistrigh sé don Ghúm i rith 1925-32: Teacht Fríd an tSeagal, 1932 (Comin’ thro’ the Rye le Helen Mathers); An Mairnéalach Dubh, 1933 (The Nigger of the Narcissus le Joseph Conrad); Ben Hur, 1933 (le Lew Wallace); An Páistín Fionn, 1934 (The Whiteheaded Boy le Lennox Robinson); Séideán Bruithne, 1935 (Typhoon le Joseph Conrad); Muintir an Oileáin, 1936 (Islanders le Peadar O’Donnell); Teach an Chrochadóra, 1935 (Hangman’s House le Donn Byrne); Díthchéille Almayer, 1936 (Almayer’s Folly le Joseph Conrad); Ivanhoe, 1937 (Ivanhoe le Walter Scott); Báthadh an Ghrosvenor, 1955 (The Wreck of the Grosvenor le W. Clark Russell); Imtheachtaí Fear Dheireadh Teaghlaigh, 1936 (Adventures of a Younger Son le E.J. Trelawny); Eadarbhaile, 1953 (Adrigoole le Peadar O’Donnell). Is in aon leabhar amháin, Séideán Bruithne agus Amy Foster, 1935, atá an dá theideal le Conrad (Clár Litridheacht na Nua-Ghaedhilge 1, 1938).Deir Niall Ó Dónaill gurbh é Peadar O’Donnell a roghnaigh Seosamh chun leabhar dá chuid a aistriú ‘nuair a bhí a shláinte ag briseadh air agus é fágtha ar bheagán saothraithe’; chreid Mac an Bheatha gur faoi dheireadh 1936 a thosaigh sé ar Adrigoole Uí Dhomhnaill a aistriú. Tugadh eagrán nua de Muintir an Oileáin amach arís sa bhliain 1989 mar shampla ar na haistriúcháin is fearr dár fhoilsigh an Gúm. Deir Gréagóir Ó Dúill in Comhar, Iúil 1990: ‘Seasann leabhair dár aistrigh sé mar chuid de litríocht na Gaeilge—Eadarbhaile ar Adrigoole le Peadar O’Donnell agus Séideán Bruithne ar Typhoon le Joseph Conrad le dhá shampla a lua.’

Gheofar cuntas beacht ar thuairimí Mhic Grianna i dtaobh an Ghúim agus na sclábhaíochta a bhain leis na haistriúcháin in Feasta, Aibreán 2002 (‘Scríbhneoirí Gaeilge Dhún na nGall agus scéim Aistriúcháin an Ghúim’ le Nollaig Mac Congáil). Is leis an bhfuath a thug sé dó a bhaineann an chaibidil ‘Mac Grianna, Ó Flaithearta, an Saorstát’ i leabhar an Bhrúnaigh: ‘Ar ndóigh, i dtaca le Mac Grianna de, ionchollaíodh duáilcí uile an tSaorstáit sa Ghúm. . . ’. Nuair a tháinig Fianna Fáil i gcumhacht i 1932, cuireadh deireadh nach mór le leabhair a bheith á n-aistriú ón mBéarla. Deir Niall Ó Dónaill: ‘Tháinig an cosc, cuid mhaith, as na gearáin phoiblí a rinne scríbhneoirí mar Sheosamh é féin ar chóras aistriúcháin an Ghúim.’ Is dóigh le Ó Muirí go raibh teacht isteach réasúnta aige ón obair ach nárbh é an sórt duine é a n-oirfeadh an córas íocaíochta dó, is é sin an t-airgead a bheith ag teacht ina chnapanna anois is arís. Deir an t-údar sin: ‘The weight of translation (and the way in which Mac Grianna threw himself into it), allied to the demands of his own original work, was beginning to place an almost unbearable strain on his mental faculties.’ Ina theannta sin, cé gur ghlac an Gúm leis an úrscéal An Droma Mór i 1932, ní raibh fonn orthu é a fhoilsiú; bhí eagla orthu go mbeadh clúmhilleadh i gceist. Meastar go mbainfeadh tábhacht i bhfad níos mó leis an saothar dá dtagadh sé amach an uair sin; níor foilsíodh é go 1969 agus bronnadh Duais an Bhuitléaraigh air. In Seosamh Mac Grianna: Aistritheoir, 2005 tá staidéar le Seán Mac Corraidh ar dhosaen de na haistriúcháin a rinne sé don Ghúm.

Deir Ó Dónaill gur tharla na heachtraí sin go léir a bhfuil cur síos orthu in Mo Bhealach Féin ach gur chuir Mac Grianna craiceann orthu; meastar gurb úrscéal dírbheathaisnéisiúil é. Níor éirigh leis an t-úrscéal Dá mbíodh ruball ar an Éan a chríochnú agus is í an abairt deiridh ann: ‘Thráigh an tobar ins an tsamhradh 1935. Ní scríobhfaidh mé níos mó. Rinne mé mo dhícheall agus is cuma liom.’ Bhí sé in aontíos le bean darbh ainm Peigí le tamall. Níltear cinnte nach pósta léi a bhí sé; bhí sise pósta roimhe sin ar mhairnéalach dar sloinne Ó Domhnaill agus tuairimítear gur beannacht na heaglaise Caitlicí amháin a bhí ar an bpósadh le Seosamh, má bhí pósadh ann. Bhí mac acu darbh ainm Fionn ach cuireadh isteach i ndílleachtlann na mBráithre Críostaí i nGlas Naíon é nuair nár fhéad an lánúin cúram ceart a thabhairt dó. Seo é an cur síos a thugann Ó Baoighill ar an bhean: ‘Bhí Seosamh pósta agus labhair mé uair amháin lena bhean chéile ar an ghuthán in Oifig Chomhdháil Náisiúnta na Gaeilge. . . . Chomh fada agus is cuimhin liom Peigí Green a thug sí uirthi féin agus bhí sí ag lorg airgid ó Dhonncha Ó Laoire le cabhrú le Seosamh. Bean chliste a bhí inti a raibh lúth na teangan aici agus inseadh ina dhiaidh sin domh go mbíodh sí i gcónaí ag maíomh as cumas Seosaimh mar scríbhneoir agus go mbeadh sí de shíor ag crá Chomhdháil Náisiúnta na Gaeilge agus Raidió Éireann agus cuid de chairde an scríbhneora ag lorg airgid. . . . Bhí mac amháin acu, Fionn, a báthadh go tragóideach i gCuan Bhinn Éadair.’

Chaith sé tamall i nGráinseach Uí Ghormáin i 1935-36. As sin amach bhí an saol go dona aige. Tá cuntas ag Mac an Bheatha ar na cuairteanna a thugadh sé air ó Iúil 1954, agus ar an gcabhair a thugadh sé dó, go dtí go ndeachaigh sé go Rann na Feirste i 1957. Solas coinnle amháin a bhí aige sa teach beag seo i gCluain Tarbh. Bhí droch-chaoi ar sheomraí agus ar throscán an tí; ní raibh Peigí in aontíos leis um an dtaca seo agus ní raibh sí in ann aon chúnamh airgid a thabhairt dó. Ba mhinic nach gceannaíodh sé ach arán ach b’fhéidir gurb í an abairt seo an cur síos is léirithí ag Mac an Bheatha ar a dhearóile a bhí a chás: ‘Measaim go mbailíodh sé na bunanna toitíní ón bhóthar nuair nach mbíodh a thuilleadh toitíní aige agus gur sa phíopa a chaitheadh sé iad.’ Bhí Donncha Ó Laoire agus Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh ar na daoine eile a d’fhéachadh le cabhrú leis. I 1959, chuir Peigí lámh ina bás féin agus an bhliain chéanna sin a bádh an mac. Cuireadh Seosamh isteach in Ospidéal Naomh Conall i Leitir Ceanainn tuairim an ama sin agus ann a d’fhan sé. Scitsifréine a bhí air, ach níor fhág sin nach bhféadfadh sé a bheith páirteach in éigsí agus i bhféiltí i nDún na nGall ar ball. San ospidéal sin a bhásaigh sé 11 Meitheamh 1990.

Diarmuid Breathnach

Máire Ní Mhurchú

Iomlán eolais thuas tógtha ón suíomh ‘www.ainm.ie’ http://www.ainm.ie/Bio.aspx?ID=1580

Leabhair Sheosaimh:

An Dochartach Dhuibhlionna & Scéalta Eile. (1925) Leigh ar líne ag https://archive.org/stream/dochartachdhuibh00macguoft#page/n3/mode/2up

Filí Gan Iomradh (1926) Oifig an tSoláthair, BÁC (cuntas ar Dhálaigh Rann na Feirste sa tseanaimsir)

An Grádh agus an Ghruaim (1929) Oifig an tSoláthair, BÁC (gearrscéalta)

Eoghan Ruadh Ó Néill (1931) Oifig an tSoláthair, BÁC (úrscéal stairiúil)

An Bhreatain Bheag (1937) Oifig an tSoláthair, BÁC

Na Lochlannaigh (1938) Oifig an tSoláthair, BÁC

Mo Bhealach Féin (1940) Oifig an tSoláthair, BÁC

Dá mbíodh ruball ar an Éan (1940) Oifig an tSoláthair, BÁC

An Droma Mór (1969) Oifig an tSoláthair, BÁC

Filí agus Felons (1987) Eag. Connolly, December (Dublin, 1987).

Aistriúcháin le Seosamh Mac Grianna

Teacht Fríd an tSeagal,(1932 ) Comin’ thro’ the Rye le Helen Mathers

An Mairnéalach Dubh,(1933) The Nigger of the Narcissus le Joseph Conrad

Ben Hur,(1933) Ben Hur le Lew Wallace

An Páistín Fionn,(1934) The Whiteheaded Boy le Lennox Robinson

Séideán Bruithne agus Amy Foster,(1935) Typhoon and Amy Foster le Joseph Conrad

Teach an Chrochadóra,(1935) Hangman’s House le Donn Byrne

Muintir an Oileáin,(1936) Islanders le Peadar O’Donnell

Díthchéille Almayer,(1936) Almayer’s Folly le Joseph Conrad

Imtheachtaí Fear Dheireadh Teaghlaigh,(1936) Adventures of a Younger Son le E.J. Trelawny

Ivanhoe,(1937) Ivanhoe le Walter Scott

Eadarbhaile,(1953) Adrigoole le Peadar O’Donnell

Báthadh an Ghrosvenor,(1955) The Wreck of the Grosvenor le W. Clark Russell

Ábhar Léirmheastóireachta ar shaothar Sheosaimh Mhic Grianna:

Riobard Ó Faracháin [Robert Farren], ‘Seosamh Mac Grianna’, The Bell, 1, 2 (Samhain. 1940), lgh.64-68

Breandán Ó Doibhlin, ‘Fear agus Finscéal: Dála An Druma Mór’, in Irisleabhar Mhá Nuad (1969), lgh.7-20;

Proinsias Mac an Bheatha, Seosamh Mac Grianna agus Cúrsaí Eile (BÁC: Foilseacháin Náisiúnta Tta. 1970)

Proinsias Mac Cana ‘An Druma Mór’, in Comhar (Bealtaine 1971), lgh.19-23;

Oilibhéar Ó Croiligh, Bealach Mhic Grianna (Corcaí/BÁC: Cló Mercier 1972), lch.47

Nollaig Mac Congáil, eag., Saothair Sheosaimh Mhic Grianna: Ailt Cuid a Dó (An Cabháin 1972)

Breandán Ó Doibhlin, ‘Fear agus Finscéal’ in Aistí Critice agus Cultúir (1974);

Liam Ó Dochartaigh, ‘Mac na Míchomhairle’, smaointe ar Mo Bhealach Féin, in Irisleabhar Mhá Nuad (Iúil 1975) lgh.13-16;

Seamus Deane, ‘Mo Bhealach Féin le Seosamh Mac Grianna’, in John Jordan, ed., The Pleasures of Gaelic Literature (BÁC/Corcaí: Mercier/RTE 1977)

Séamas Ó Saothraí, ‘Tar Éis Leathchéad Bliain’, léirmheas faoi Anraí Mac Giolla Chomhaill, eag., Dochartach Duibhlionna agus Scéalta Eile in Books Ireland (Meith 1977) lgh.118-19

Nollaig Mac Congáil, ‘Foinsí Béaloidis I nGearrscéalta Sheosaimh Mhic Ghrianna’, Comhar (Feabhra 1978)

Anraí Mac Giolla Chomhaill, eag., Saothair Sheosaimh Mhic Grianna, Cuid a hAon, Dochartach Duibhlionna agus Scéalta Eile (Coise Foilsitheoireachta Chomhaltas Uladh 1979) lch. 43

Seán Ó Mórdha, eag, Scríobh 5 [Mac Grianna Eagran Speisialta (Baile Átha Cliath: Clóchomhar 1981) (San áireamh: Declan Kiberd, ‘Mo Bhealach Féin, Idir Dhá Thraidisiún’, agus Liam Ó Dochtartaigh, ‘Mo Bhealach Féin: Saothar Nualtríochta’

Donnchadh Ó Baoill, ‘Druma Mór na Filíochta’, in Nua-Aois (BÁC NUI: Cumann Liteartha 1986) lgh 20-29

Cathal Ó Háinle, ‘An Druma Mór’, in Litríocht na Gaeltachta, Léachtaí Cholm Cille XIX (Maigh Nuad 1989) lgh.129-67;

Séamus Mac Annaidh Rubble na Mickies (1990) (Cuairt go Leitir Ceanainn ar Sheosaimh)

Nollaig Mac Congáil, eag., Seosamh Mac Grianna, ‘Iolann Fionn’: Clár Saothair (BAC Coiscéim 1990), 103pp. Aistí le Cathal Ó Háinle, Seosamh Watson, Liam Ó Dochartaigh, Diarmaid Ó Doibhlin, Pol Ó Muirí, Liam Lillis Ó Laoire, Eoghan mac Einrí.

Pól Ó Muirí, Flight from Shadow: The Life and Work of Seosamh Mac Grianna (Belfast: Lagan Press 1999), 213pp.;

Alan Titley, ‘Unfavourite Son’, review of Pól Ó Muirí, A Flight from Shadow: The Life and Works of Seosamh Mac Grianna, in Books Ireland (March 2000), pp.65-66

Fionntán de Brún, review of A Flight from Shadow: Life and Work of Seosamh Mac Grianna (Lagan 1999), in Fortnight [Belfast] (April 2000), pp.29-30;

Fionntán de Brún, Seosamh Mac Grianna: An Mhein Ruin (An Clochomhar 2002).

Pól Ó Murií, Seosamh Mac Grianna: Míreanna Saoil (Cló Chonnachta 2007) lch 180.

Catríona MacKernan, review of The Big Drum, in Books Ireland (Summer 2010), pp.133-3

Aistriúchán ar leabhar Sheosaimh:

Hughes, Art J. (2010) (Aist) (An Druma Mór)

The Big Drum, Clólann Bheann Mhadagáin.

Léargas ghairid ar an saothar seo ag an nasc seo a leanas:

http://seosamhsonar.blogspot.ie/2010/04/druma-mor-big-drum.html

Suímh idirlín le heolas ar Sheosamh:

Ainm.ie Saol & Saothar Sheosaimh: http://www.ainm.ie/Bio.aspx?ID=1580

Déanann Éamonn Ó Dónaill leirmheas ar ‘Míreanna Saoil’ le Pól Ó Muirí: http://www.beo.ie/alt-leabharmheas-10.aspx

Páipéir Sheosaimh Mhic Grianna 1933-1957 (1972) 45 mír, Leabharlann Shéamais Uí Argadáin Ollscoil Éireann Gaillimh:

http://vmserver52.nuigalway.ie/col_level.php?col=G42

Treoir Idirlín ‘Searc’ chuig Éire sa 20ú haois: